As we approach not only the end of a decade and the end of a century but a new millennium itself, there are moments when art seems to have reached a terminus — when it appears there is nowhere further to go in the exploration of form, language, or the ontology of the image. And then, unexpectedly, someone like Gareth Ellison emerges from the Cumbrian drizzle, bringing with him a machine that thinks in visual metaphors, and with it, a whole new terrain of possibility. His recent work, The Mathematics of Chaos (1997), now installed at the Manchester Centre for Experimental Image Studies, is both a culmination and a departure — a testament to the capacity of algorithmic systems to produce, almost in spite of themselves, a kind of machine mysticism that truly heralds a new epoch.

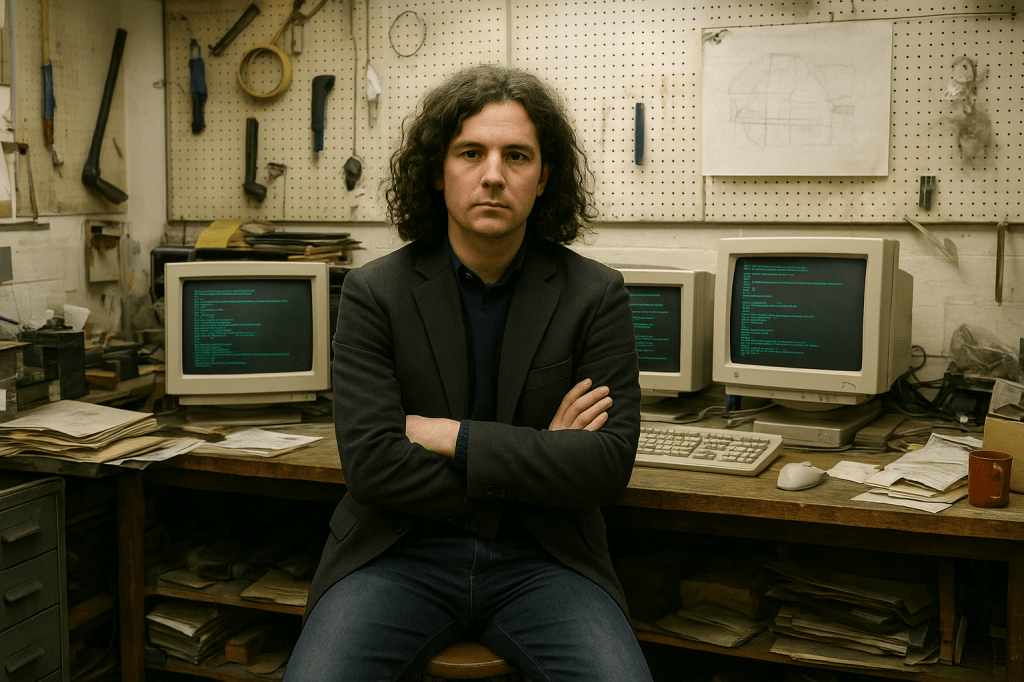

Born in Ulverston in 1968, Ellison’s biography has by now assumed the status of anecdotal folklore in the London art scene. His disavowal of early art instruction — he reportedly endured a disenchanting teacher named Mr. Newnham at junior school, a figure he once described as “an evangelist for beige and boring pottery.”1 — has been endlessly recycled by critics seeking to frame his later embrace of computational determinism as a kind of revenge upon pedagogy. This early disenchantment with institutional art training perhaps explains his later recourse to systems thinking, and it was while working at the neighbouring town’s shipyard as a draftsman that Ellison created the first iteration of his Automathicon: a hybrid apparatus comprising early home-computing programming, algorithmic flowcharts, and an extensive “library of contradictions” drawn from physics, theology, and speculative fiction.2

It is from this ever-mutating matrix that Ellison’s latest piece, The Mathematics of Chaos, was born. Ellison has described it as “a visual field generated by recursive non-linearity, but stabilised through aesthetic decision-making”3 — a typically evasive statement that belies the extraordinary precision of the result. The work’s surface is a densely layered palimpsest of line, tone, and directionality: arcs intersect with vectors, spirals collapse into themselves, and linear striations appear to pulse outward from an unseen attractor. It is as though a tornado of pure information has been momentarily frozen in graphite.

What distinguishes Ellison from the techno-fetishists of the so-called “digital sublime”4 is his refusal to surrender authorship entirely to the machine. The Automathicon, while generative, is also conversational — a prosthetic collaborator whose operations must be interpreted and sometimes resisted. “The machine is my unreliable narrator,” he told The New Parameters Review in 1995.5 This dialectical relationship between randomness and intention is the crux of Ellison’s achievement. The artist does not merely illustrate chaos; he orchestrates it, allowing the algorithms to sketch the scaffolding while his own painterly intuition inflects the result. To create, in Ellison’s system, is not to dominate material but to surrender gracefully to its potentialities.

The Mathematics of Chaos thus occupies a curious space between control and surrender, reminiscent of what Rosalind Griever called “the neo-sublime of computation”6 — an aesthetic predicated not on transcendence but on the recognition of systemic beauty within disorder. The work’s grayscale gradients, produced through successive layers of carbon transfer and photomechanical reproduction, oscillate between the architectural and the organic. One is tempted to read the composition as a map of thought itself: an exploded diagram of cognition rendered visible.

Ellison’s earlier works, such as Probabilistic Sculpture No. 4 (for Babbage) (1989) and The Ontology of Dice (1995), hinted at this same tension, though their outcomes were more overtly diagrammatic. In The Mathematics of Chaos, however, Ellison seems to have transcended the literal apparatus of the machine and entered the realm of what I would term algorithmic expressionism. His gestures, though derived from formulae, retain a residue of human urgency — a trace of the hand resisting the tyranny of the code.

Critics have often compared Ellison’s methodology to the chance operations of John Cage or the systems painting of Sol LeWitt. Yet such parallels miss the crucial element of Ellison’s practice: the feedback loop of meaning. While Cage sought to remove intention and LeWitt to formalise it, Ellison builds intention back into the circuit. The Automathicon does not replace the artist, it simply amplifies his indecision. Each new equation, each randomised data input, becomes another opportunity for Ellison to negotiate with uncertainty and to ultimately aestheticise the process of choosing itself.

One of the most intriguing aspects of The Mathematics of Chaos is its visual refusal to stabilise. As the viewer’s eye follows the centrifugal sweep of its lineation, the image seems to oscillate between two and three dimensions, between map and maze. The flattening bands that radiate from the centre — almost barcode-like in their regularity — threaten to annihilate the very depth that the central vortex creates. The result is an experience of visual vertigo: an optical analogue to what Ellison calls “the mathematics of the unfinishable”7 which perhaps is responsible for a peculiar kind of melancholy experienced after viewing.

Ellison’s fascination with emergence and indeterminacy aligns him with a broader late-century tendency toward what has been termed computational romanticism — a desire to re-enchant the digital by recovering its aesthetic potential. But Ellison’s work is distinguished by its moral seriousness. Unlike many of his contemporaries in the generative art scene, he refuses irony. The Automathicon is not a toy but a philosophical instrument, probing the interface between causality and chance. “All systems dream of collapse,” Ellison remarked during a lecture at the Royal Society of Art (1994), “but collapse is the system’s most articulate expression.”8

In The Mathematics of Chaos, collapse becomes form. What at first glance appears as noise reveals itself, upon sustained contemplation, to be a visual syntax of failure and adaptation. Ellison’s genius lies in showing that randomness is not the enemy of order but its precondition. If the twentieth century began with the machine as emblem of control, Ellison ensures it ends with the machine as co-conspirator in the act of creation.

- Ellison, quoted in Croft, P. “From Shipyards to Simulations,” Northwestern Arts Quarterly, Vol. 12, No. 3 (1988), p. 28. ↩︎

- Marsh, L. “Automathicon: Machines That Make Themselves,” Art Journal of the North, Vol. 5 (1995), p. 18. ↩︎

- Ellison, G. Artist’s Notebook: 1992–93, unpublished manuscript, Ellison Archive, Carlisle. ↩︎

- Dant, R. The Digital Sublime and its Discontents (Leicester: Quarry Press, 1996), p. 72. ↩︎

- “Systems of Self-Contradiction: A Conversation with Gareth Ellison,” The New Parameters Review, Vol. 9, No. 1 (1995), pp. 4–9. ↩︎

- Griever, R. “The Neo-Sublime of Computation,” Transmodern Aesthetics, Vol. 7 (1996), pp. 55–64. ↩︎

- Ellison, G. “The Mathematics of the Unfinishable,” lecture, Royal Society of Art Systems, 1994. ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎