The figure of Marlowe Nyman occupies an uncertain place in the annals of modern musical history. His story is rarely told in music circles, and when it is it is treated more as whispered folklore than documented fact. Yet the sheer recurrence of his story across disparate sources suggests that, however distorted by myth, it conceals a core of truth. While his name is absent from standard conservatoire curricula and his works are rarely catalogued in public collections, he persists like a revenant in the footnotes of more eccentric studies. Among those who pursue the liminal margins of musicology—where sound, sensation, and metaphysics blur—Marlowe is thus cited with an awe mingled equally with dread.

To understand the phenomenon attributed to him, one must begin with the paradox that defined his existence: he was blind from birth and yet was said to perceive the world through a heightened interplay of his other senses: smell, taste, touch, hearing, and, most mysteriously, a capacity to feel music. As such, from childhood it is generally agreed that he demonstrated an uncanny aptitude for the piano. Unlike other prodigies —if we are to credit the fragmentary testimonies preserved in the so-called Carfax Papers (now housed in a restricted archive of Brichester Collegium)—Marlowe denied that he “created” music. He believed that music was never composed but discovered, as though the world were a lattice of hidden melodies awaiting discovery by a sufficiently attuned medium: “Music displaces the air, you know. It changes reality.” he is quoted as saying.1

This notion, that musical structures pre-exist in some transcendent dimension, has antecedents in both Platonic metaphysics and certain mystical traditions. One recalls Pythagoras’ doctrine of the musica universalis, wherein the movements of celestial bodies are said to generate a harmony inaudible to common ears. Marlowe’s peculiar genius, if we follow the few reliable reports, was to experience fragments of this hidden harmony through a synaesthetic interplay of his remaining senses. Music was not for him a construction but a form of excavation. “He did not invent,” remarks an anonymous contemporary in The Horlick Manuscript, “he uncovered.”2

From an early age, Marlowe’s virtuosity at the piano established him as a prodigy and his unique insights brought him intense admiration at the now-defunct Holcroft Conservatoire. Accounts from his instructors describe his playing as “captivating beyond endurance.”3 Yet prodigious talent rarely flourishes unopposed, and among his peers jealousy fermented. A duel-recital with K. Durlacher, an accomplished pianist in his own right, seems to be the genesis of the most infamous rivalry. Both pianists performed Chopin études, but critics noted that while Durlacher dazzled with technical mastery, Marlowe’s interpretation seemed “as though Chopin had concealed a second piece beneath the first, and Marlowe had uncovered it.”4 The rivalry with Marlowe was further compounded by their mutual involvement with the violinist Deborah H, and concluded in a particularly brutal act too prevalent and entwined in the crescendo of the mystery to be ignored. Hospital records from Brichester General confirm that a young male pianist was admitted in 1882 with a severely mutilated hand. The cause? Razor blades had been inserted between every key of his piano. Marlowe’s hand was gashed so severely that his dexterity and capacity for performance was permanently impaired, but whether Durlacher acted alone or in conspiracy with Deborah H is uncertain and the guilt of neither party was ever proved. Nevertheless every surviving narrative treats the maiming as the crucial turning point in Nyman’s career.5

From this moment, Marlowe’s trajectory shifts. Unable to perform with the same fluency and deprived of the tactile ecstasy of performance, he turned inward to composition, research, and—according to certain dubious manuscripts—ritual. Here we reach the crux of his peculiar contributions, for his compositional method diverged radically from accepted practice. Four Canons in Negative, for example, featured a cycle of canons in which the leading voice begins after the follower — a reversal that baffled audiences but gained cult admiration among avant-garde circles in London following its debut in 1891. Studies in Silent Resonance, which involved a series of short pieces built around intervals of silence using the sustain pedal to imply harmonics that were “felt” more than heard, further helped Marlowe cement his reputation when it was first performed in 1896. Copies of both survive only in incomplete manuscript at the Holcroft Estate Collection.

As a professor at a provincial college, Marlowe’s years as a scholar of ethnomusicology are sparsely documented but richly embroidered by later commentators. His notebooks, fragments of which also survive in the Holcroft Estate Collection, obsess over music as puzzle and key: “Every note uncovers a gate and every dissonance conceals a chamber.”6 He read Gérard de Nerval, who claimed that recomposing scales could “gain power in the world of the spirits.”7 He collected the works of marginal theorists such as Roccó Peverelli and de Robataille, who speculated that certain tonal clusters could pierce the veil of ordinary perception. Thus, convinced that true melodies lay hidden within the fabric of existence, Marlowe began experimenting with what he called “extractional techniques.” Fragmentary lecture notes, attributed to his late-period seminars, suggest that he believed music could be brought forth not merely through sound, but through corporeal sacrifice.8 The phrase “get it out of himself” appears repeatedly in these documents, suggesting a belief in music as immanent within the flesh.

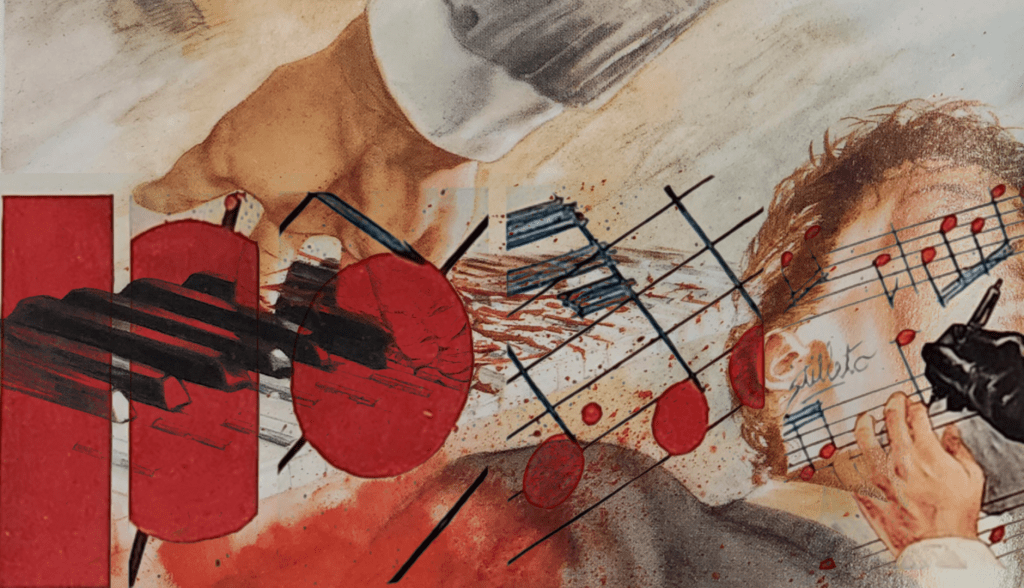

The most disturbing evidence of this approach comes from Greil’s monograph The Vanishing Score, a manuscript preserved only in blurred photographs taken before its disappearance from the Basel Musikwissenschaftliches Archiv. Clearly scarred both physically and mentally from his maiming, the monograph alleged that Marlowe constructed a crude “door” covered in razor blades over which he dragged his naked body in a ritualised crawl. Allowing his blood to fall upon manuscript paper, each droplet was then converted into erratic notation, and notation into sound, thus forming what would become Requiem in Fragments aka the Red Score.9

What followed at the premiere of this score has been the subject of considerable speculation, often sensationalised beyond credibility. The performance was reportedly held at Aegis Concert Hall in Brichester c. 1902, with the piano entrusted to Durlacher himself. The audience, drawn from the fashionable and the informed, expected avant-garde experiment. What they received was something else entirely.

Marlowe’s work has consistently been described as frantically minimalist, and those few scholars who have attempted to research the performance insist that what occurred was a hallucination, triggered by infrasound or dissonant repetition. Others argue that the piece achieved what Marlowe had long claimed: the revelation of a deeper stratum of reality through sound. Nonetheless, multiple testimonies—letters, diary entries, and one fragment from a coroner’s report—attest that the audience at the performance experienced a collective breakdown. In performing the piece, Durlacher is said to have entered into a manic reverie of repetition and tempo increase until at its crescendo the entire orchestra collapsed into immediate death. Attendees reportedly exhibited symptoms ranging from hysteria to dyskinesia with sources insisting that the select audience at the performance never recovered. Marlowe himself is reported to have sat calm amidst the chaos, untouched, even as the hall dissolved into carnage.10 The performance itself, naturally, was never repeated, and no sheet music survives as far as this biographer is aware outside of a tantalising snippet based on blurred imagery from The Vanishing Score.

(After painstaking background research in the course of digitising this essay, the aforementioned snippet has been identified and crudely re-interpreted via Musical Instrument Digital Interface. It is embedded below purely as a curio – The Custodian).

One must tread carefully here, for hyperbole is a constant hazard in Marlowe studies. Yet if one accepts that certain tonal structures possess an inherently destabilising effect upon the psyche—as argued in Auerbach’s On Forbidden Intervals11—then the possibility of such catastrophic consequences cannot be wholly dismissed. The question arises: what, precisely, did Marlowe uncover? Was his composition a work of aesthetic extremity, pushing tonal repetition to the brink of human tolerance? Or did he, as some have chillingly suggested, brush against a deeper stratum of reality, unlocking not merely an auditory but an ontological threshold?

It is here that the oft-quoted question emerges: “Is there a secret song at the centre of the world?” The phrase, attributed to Marlowe himself, first appears in the correspondence of Professor Elias Venn of the Brichester Collegium. Venn wrote, cryptically, that Marlowe had “glimpsed the lattice of sound by which the cosmos is stitched together” and that his music constituted “a partial, terrible unveiling.”12 Sceptics dismiss such accounts as rhetorical embellishment, yet the persistence of the idea—that beneath the surface of experience lies a primal melody whose revelation could induce madness—cannot be easily ignored.

Marlowe himself vanishes from the record shortly after the performance. Theories abound: that after witnessing the consequence of his composition he retreated into seclusion; that he perished due to his own ritualistic methods; even that he transcended his corporeal form and entered some incommunicable dimension of sound at the crescendo of Requiem in Fragments. None of these conjectures can be substantiated and all that remains is the whisper of his legend: fragmentary manuscripts, contradictory testimonies, and a lingering unease among those who probe the boundaries of musicology.

Whether Marlowe Nyman was a genius tragically undone by obsession, or a reckless experimenter who touched upon forces beyond comprehension, is ultimately undecidable for the sparse records allow no final judgement. Yet the questions raised by what little we know of his life and work persist in their unsettling implications. If music is not a human invention but a discovery, what lies yet undiscovered? And if Marlowe’s fate is any indication, should such discoveries remain hidden? The myth, if myth it is, endures precisely because it gestures towards the possibility that sound is not merely art but aperture: that through music, one might pry open the very fabric of existence. Is there a secret song at the centre of the world? Marlowe believed so. Whether we should seek to hear it ourselves is another matter entirely.

- Carfax Papers, MS. CXII, Brichester Collegium Archive, fol. 23. ↩︎

- Anonymous, The Horlick Manuscript, privately circulated typescript, c. 1880. ↩︎

- Letters of Headmaster Elgar Thornycroft, Holcroft Conservatoire (Univ. of Gant House Collection). ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- See conflicting testimonies in Mallory, P., Crimes of the Conservatoires (Oxleigh: Ferrant Press, 1953), pp. 214–19. ↩︎

- Nyman, M., “Theories on Extraction,” in Uncatalogued Papers (Holcroft Estate Collection, Box III). ↩︎

- Gérard de Nerval, Aurélia (Paris: 1855). ↩︎

- Nyman, M., “Notes on Extraction,” in Uncatalogued Papers (Holcroft Estate Collection, Box IV). ↩︎

- Greil, R., The Vanishing Score: Studies in Lost Music (Basel: Kythera Verlag, 1910). ↩︎

- “Inquest into Disorder at the Aegis Concert Hall,” Coroner’s Report Fragment, Brichester County Records Office, 1902. ↩︎

- Auerbach, H., On Forbidden Intervals (Vienna: Helios Akademie, 1927), esp. Ch. III. ↩︎

- Venn, E., Letter to M. Carfax, 17 October 1899, Carfax Papers, fol. 47. ↩︎