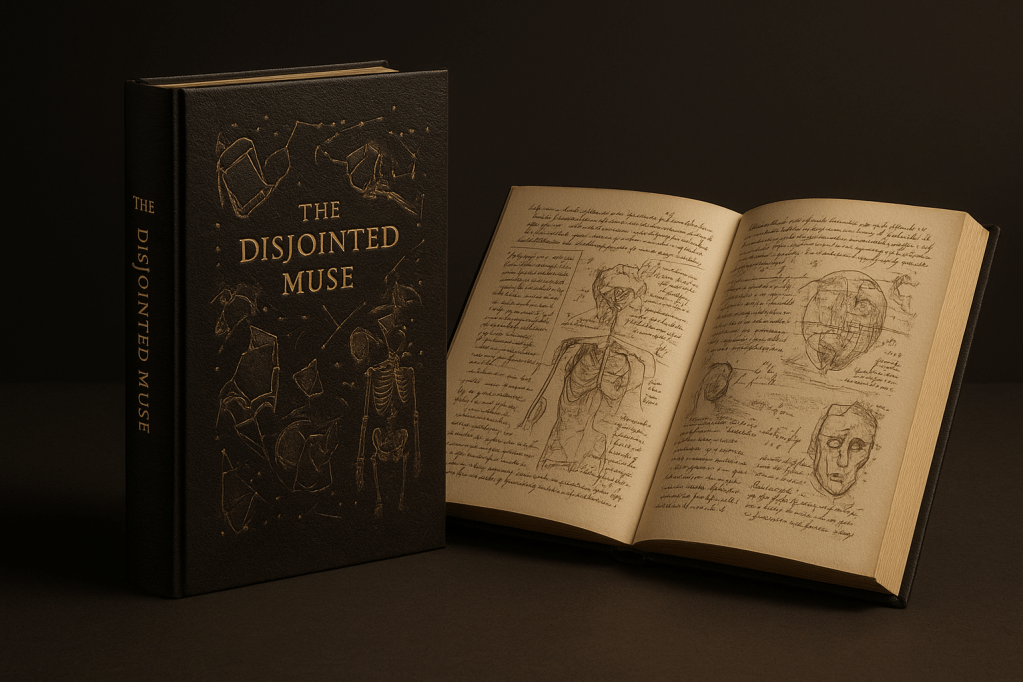

Posthumous publications often arrive with the muted air of summation, the gentle reverence of epilogue. The Disjointed Muse*, however, is no such coda. Instead, this newly compiled collection of letters, essays, sketches, and marginalia from the late painter Ludovico Klementine (October 1927 – disappeared October 1974 – declared dead October 1981) detonates a long-buried mine at the intersection of art, theory and the metaphysical fringe. It repositions Klementine not merely as a painter of the unconscious, but as the unconscious made manifest—raw, unresolved, and utterly indispensable to understanding the darker tributaries of 20th-century modernism.

Klementine and his canvases—ostracised by the artistic community in his lifetime, transformed into a cult figure by the same community post-disappearance—have hitherto resisted narrative and intention altogether. What The Disjointed Muse reveals, through a judicious curation of his private writings and annotated reproductions of key works, is that this resistance was not indolence but ideology. At the heart of Klementine’s approach lay an absolute adherence to Anomaly Theory: a multifunctional approach conceived by Dr. Walter E. Crofton, fringe scientist and head of the New England Experimental Research Institute, which rejects traditional pattern-recognition as the means of interpretation and instead espouses anti-patternicity—a deliberate search for order within the collapse of discernible form. During his lifetime, Klementine neither formalised nor evangelised this radical aesthetic framework but it’s now clear it permeates his oeuvre.

To the casual observer, Klementine’s pieces (notably The Supplicant Spiral and Dinner With the Invisible Midwife which were both completed during a self-imposed exile in Trieste in the 1960s) appear as chaotic concatenations of unmoored iconography: skeletal marionettes, melting staircases, ecclesiastical diagrams rendered in bile tones. Yet, as The Disjointed Muse compellingly argues, this disjunction is the method. The painter’s notes speak obliquely of an unconscious alchemy by which disparate motifs—objects drawn from his dreams, memories, even auditory hallucinations—coalesce into a whole that defies structural expectation, yet compels emotive coherence.

But it is Klementine’s entries, coupled with the frantic body of work he produced after witnessing Dr. Crofton’s lectures in 1971, which are particularly revelatory. In one, he alludes to “the rupture in the veil”—a reference both spiritual and neurological, possibly alluding to a breakdown or psychotic episode. In another, he writes: “We name a thing a ruin only because we cannot read the blueprint of its becoming.” This is the axis upon which Anomaly Theory pivots: a conviction that apparent chaos is a cipher, that meaning emerges not from resemblance to the real but from its fracture.

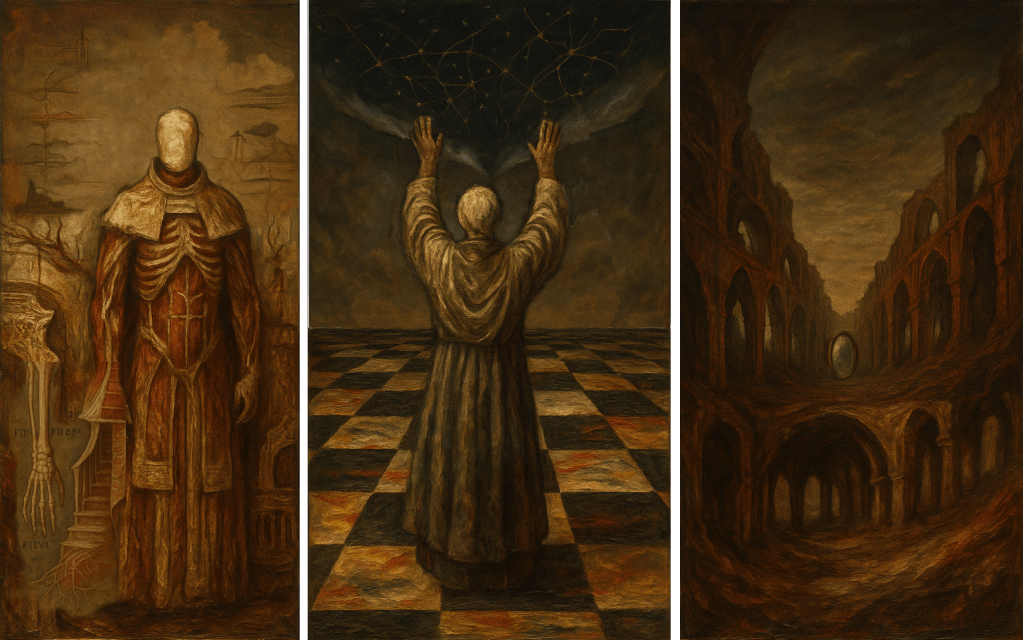

Take Saint Erasmus Folds the Sky (1972), painted during his most fervent period. The canvas, a monumental triptych, was inspired by a recurring dream in which a figure in clerical vestments undoes the night at its hidden seam, revealing a second darkness beneath. Panel I brings to mind a corrupted anatomy textbook refracted through mysticism and delirium, the faceless ghoul draped in clerical vestments made entirely of flayed anatomy has had its features scraped away, as if censored by the canvas itself, as he watches the undoing in Panel II. The titular moment occurs here and the gesture is where the triptych earns its sacred unease: above the rift floats a tangle of gold filament, like a map of constellations without stars—an attempt, perhaps, to give shape to the unshaped. It is also notable for reintroducing the infamous “bleeding chessboard” motif Klementine originally used to great effect in The Cartographers of Sleep (1966). The final panel presents a world wholly undone where a mirror—out of place yet wholly belonging—hangs suspended. It does not reflect, it absorbs, and the cracks spread not from impact but from the tension of being observed.

Klementine himself described the triptych as “A vision received, not imagined. There is something beneath the sky. I do not know what it is. But I know it dreams of us wrongly.” It was through the lens of Anomaly Theory that he could interpret this terror—not by rendering it coherently, but by resisting the very impulse to make it intelligible.

Like all of Klementine’s mature work, it is concerned with the failure of perception and the violence of revelation. The application of Anomaly Theory here can be found in its disjointed motifs—anatomy, geography, ecclesiastical ritual—which do not logically relate, but together form a cohesive, felt meaning. This is not abstraction, but a new kind of reality, one born of error, fracture, and unresolvable paradox.

The editors, Helene Ramstadt and Dr. Owen Thill, have wisely avoided any sanitisation of Klementine’s more difficult edges. His writings can be elliptical, paranoid, occasionally troubling. He muses on “the necessity of forgetting shape” and recounts feverish dreams of “cathedrals built from screams.” One particularly unnerving entry describes a canvas he abandoned because “it began to look back.” Yet even these moments are framed not as pathology but as part of a deeper quest: to express what he once called “the absolute reality beneath perception—the sacred disunity of things before the eye resolves them.”

This dovetails into Of Whom the Mirrors Dream (1974), his final major work which was left incomplete or completed prior to his disappearance depending on which side of the critical fence you fall. For all its size, it is a very claustrophobic painting. It shows a room with a centralised, glowing mirror which draws the eye and yet this mirror reflects nothing: it is a dim opalescent void, painted in thin glazes that shimmer between pearl and blood. Scattered across the composition are mirrors of different kinds yet none reflect the environment they’re in. Instead, they show other, disconnected spaces: a forest in winter, a scorched hallway, a ceiling fan turning slowly in darkness. One mirror, near the bottom left, reflects the painting itself. And though Klementine was neither the first nor last to attempt this recursive motif it is unsettling: the reflection is slightly wrong, the angle is off, and the frame is warped. Connecting them all, delicate threads of gold leaf stretch from mirror to mirror like invisible currents of memory or thought, barely perceptible under dim lighting. These lines intersect to form a constellation of absence. His journal from the period suggests a near-complete breakdown in mental cohesion: “The mirror does not show what is there, but what it has dreamt in silence. I am painting the dreams of the things that have watched us in them.” This is Anomaly Theory in extremis: the absence of subject becomes the subject and the distortion is the unity.

Throughout The Disjointed Muse, we find evidence that Klementine’s method was never outright madness but a controlled descent into it: an approach that cohered when a scientific principle finally framed his disjointed vision. The editors, to their credit, present the man as he was: haunted, yes, but deliberate; elusive, yet devout in his pursuit of a deeper kind of truth. His journals speak constantly of “the real behind the real,” and of a longing to “paint the itch beneath vision.”

This is perhaps the most radical implication of The Disjointed Muse: that Klementine’s true subject was not the world as seen, but the substratum of being that recoils from visibility. In this sense, his work anticipates post-structuralist concerns with signification and even flirts with metaphysical nihilism. And yet it never surrenders to despair. For all their uncanny desolation, his paintings pulse with something sublime and stubbornly animate as if they are themselves searching for the viewer who might complete them.

Klementine once dismissed art critics as “cartographers of fog.” The Disjointed Muse does not dispel that fog, but neither does it retreat from it. Instead, it lights a candle deep within, revealing in flickers the contours of an artist who refused coherence, not out of contempt, but as a form of reverence for the unknowable.

This is not a comforting book. It is, however, a necessary one. In its strange, spiralling pages, we are offered the rarest of gifts: a glimpse at the machinery of an unique mind, and perhaps, in that glimpse, the outlines of a truth more absolute than sense itself.

*The Disjointed Muse was originally published in a limited print run. This book is no longer in circulation and remains out of print. – The Custodian