Alaric von Stille, who died in 1976 aged 70, was one of the 20th century’s most enigmatic and divisive architects. A pioneer of surrealist architecture, von Stille redefined the role of buildings not merely as structures but as provocations—monuments to the subconscious and absurd. His designs defied gravity, logic, and convention, producing works that have been called everything from “masterpieces of dream logic” to “unlivable monstrosities.”

Having written Alaric von Stille’s obituary for this publication nearly five years ago (published in Sokal Nouveau #177 – The Custodian.), this essay aims to offer a reappraisal of his designs within the frameworks of poststructuralist critique and late-surrealist hermeneutics, foregrounding the liminal oscillation between functionality and absurdity that characterised his architectural oeuvre. By interrogating von Stille’s destabilisation of spatial semiotics, this study seeks to reposition his corpus not as the eccentric detritus of avant-garde experimentation but as a profound engagement with the epistemological crises of mid-20th century European modernity. Using a synthesis of referentialism and selective historiographical reconstruction, this article advances the argument that von Stille’s edifices were not merely loci of habitation but symbolic matrices of collective psychogeographical dissonance.

Toward a Deconstructive Praxis of Surrealist Architecture

The architecture of Alaric von Stille has, until recently, occupied a liminal space in the historiography of 20th-century European architectural movements, eclipsed by the functionalist orthodoxy of Le Corbusier and the aesthetic monumentalism of mid-century brutalism. Traditional critiques have too often elided von Stille’s subversions as eccentric anomalies within the otherwise progressive teleology of modern architecture.1 This oversight, as I shall argue, stems from an ontological failure to engage with von Stille’s buildings as discursive articulations of surrealist praxis, operating within the metanarratives of both spatial disruption and psychoanalytic architecture.

Drawing from the “absurd materialism” articulated in von Stille’s Manifesto (of the Absurd Edifice) (1933), as well as the critical methodologies of Jacques-Félix LaGrange’s oft-neglected treatise Architectura Dadaista (1964), I propose that von Stille’s work constitutes a critique of logocentric architectural paradigms. Specifically, his approach was informed by the dialectical interplay between Duchampian conceptualism, Bretonian surrealism, and a latent phenomenological resistance to the rationalism inherent in Bauhaus functionalism.

Villa Vertigo and the Ontology of Disorientation

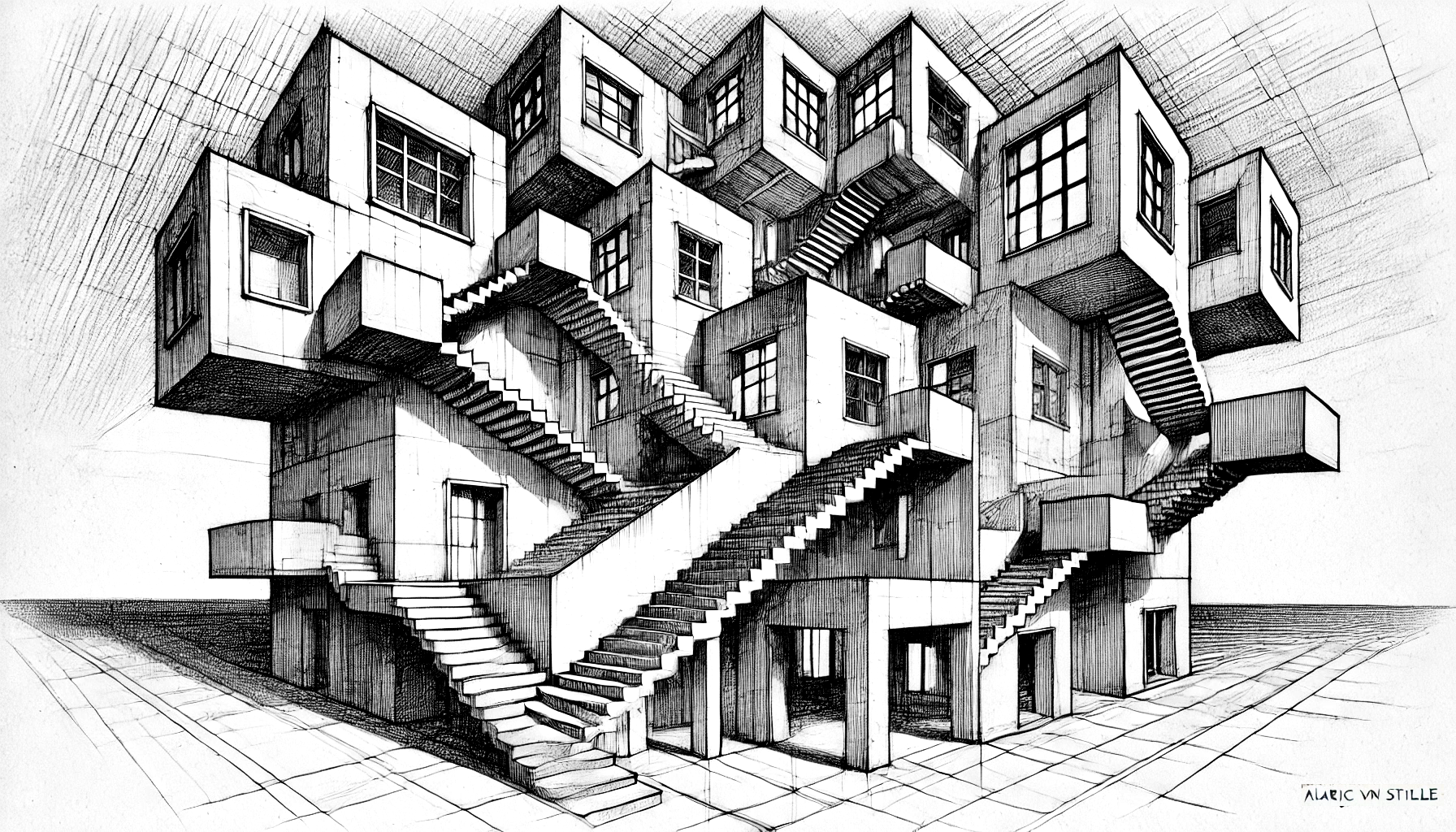

The inaugural moment of von Stille’s mature architectural idiom, Villa Vertigo (1935), provides a paradigmatic example of his attempt to destabilise the viewer’s spatial and perceptual coordinates. Traditional architectural analysis has critiqued Villa Vertigo as an uninhabitable folly; indeed, the structure’s leaning walls, labyrinthine staircases, and non-Euclidean geometries present a deliberate affront to utilitarian expectations. However, when viewed through the lens of Derridean différance, the Villa emerges as a site of ontological rupture, wherein architectural form signifies not presence but the perpetual deferral of coherence.

As Kroegemann has suggested, the Villa’s architectural semiotics instantiate a “heterotopia of deferred subjectivities.”2 The disorienting interplay of space and absence mirrors the disintegration of rationalist paradigms, a theme likewise evident in Marcel Duchamp’s conceptual reconfiguration of the ‘Readymade’. The floor plan itself suggests a fractured, disconnected layout with rooms disconnected, pathways looping back on themselves, and corridors leading to dead ends, giving the structure an unsettling feeling as though it was built without concern for spatial flow. For von Stille, Duchamp’s play of signification within the Fountain (1917) finds architectural corollary in the Villa’s deliberate inversion of structural hierarchy: its staircases ascend to nowhere, its windows reveal walls instead of vistas, its walls are tilted at odd angles to give a sense of instability and disorientation, and its ceilings slope downward as though burdened by their own existential futility.

Emphasising the tension between structure and chaos, the Villa’s fragmented spatial logic reflects what von Stille himself referred to as “psychogeographical trespass” in his 1933 Manifesto. Here, the structure acts as a site of cognitive estrangement, compelling its occupants to negotiate the dialectical tension between spatial expectation and lived experience.

The Labyrinthine Library and the Textuality of Space

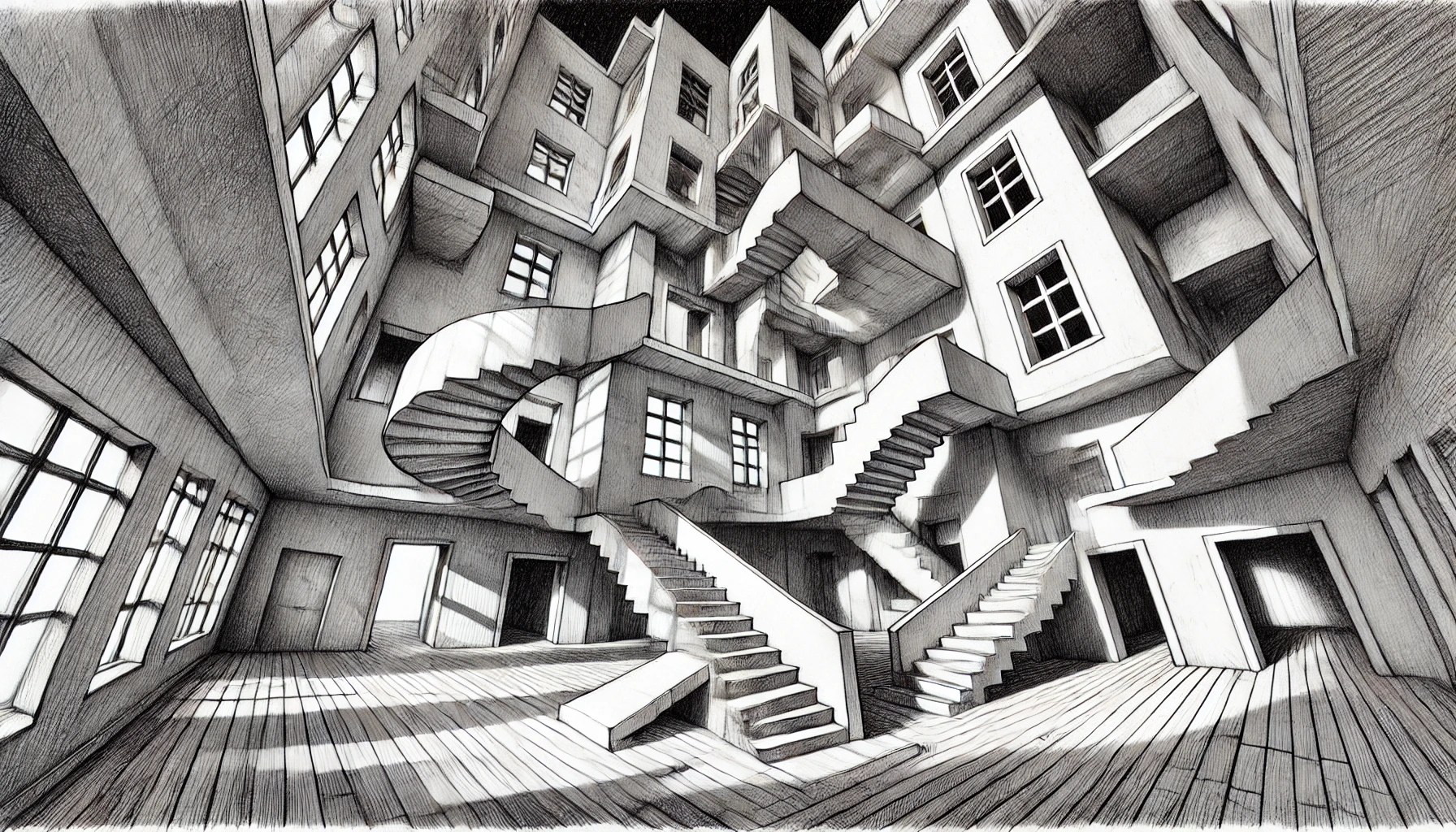

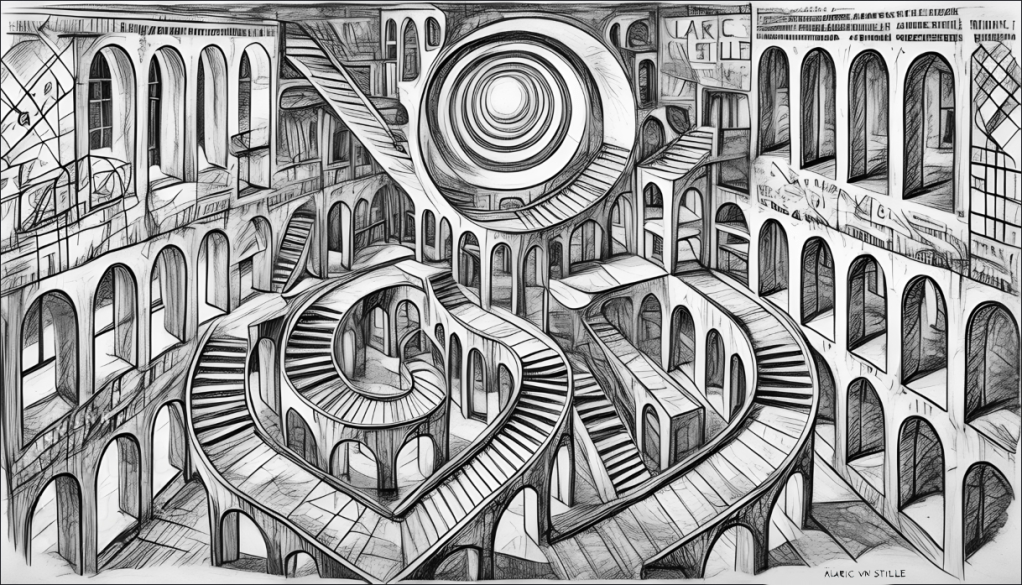

von Stille’s Labyrinthine Library (1946), constructed amidst the postwar reconstruction of Rotterdam, epitomises his synthesis of surrealist absurdity with utopian aspiration. As with Villa Vertigo, the library’s architectural schema eschews traditional hierarchies, presenting instead an assemblage of spiralling corridors and recursive staircases. Whereas conventional library design seeks to impose order upon knowledge, von Stille’s labyrinthine structure performs the opposite function: it literalises the infinite deferral of meaning, evoking Borges’s Library of Babel (1941) as a conceptual antecedent.

The entrance—a central spiralling core, much like a vortex—unravels into multiple corridors radiating from a central atrium. These corridors, which intertwine and overlap, then creates a chaotic, maze-like structure that stretches into infinity. The library’s surfaces feel almost organic, like worn stone or crumbling plaster. Some areas feature deliberate cracks and imperfections, as though the building itself was already an old, forgotten place that has been restored, but not with any regard for traditional preservation. The library itself does not follow traditional rectangular or square plans, but instead opts for irregular, organic shapes. Curved walls and floors distort conventional architectural geometry with recursions of staircases not leading upwards in any typical fashion, but instead leading into further sections of the labyrinth thus breaking up the vertical space with strange shifting levels and platforms.

Drawing upon Lacanian psychoanalysis, it is possible to situate the Library within the register of the Real, wherein its spatial impenetrability signifies the absence of symbolic closure. The Library, in this reading, becomes not a repository of knowledge but a symbolic instantiation of its impossibility. This reading finds further support in von Stille’s use of what has been termed “architectural palimpsest”: the layering of textual inscriptions upon the Library’s walls sees fragments of Latin aphorisms, geometrical formulae, and surrealist poetry collide in an illegible cacophony. These fragments of knowledge, with lines of text that trail off or are interrupted by other inscriptions, make it impossible to discern a single, clear meaning.

As D’Alençon has argued, the Library’s spatial and textual disjunctions function as “performative aporias” that enact the failure of totalising epistemologies.3 von Stille’s deliberate undermining of legibility within both the spatial and semiotic domains aligns his work with the surrealist rejection of rational coherence, offering instead a celebration of the absurd. Ultimately, you are not merely looking at a library but directly experiencing the fragmentation of thought and knowledge.

Phantom City: Utopian Absurdity and Urban Mirage

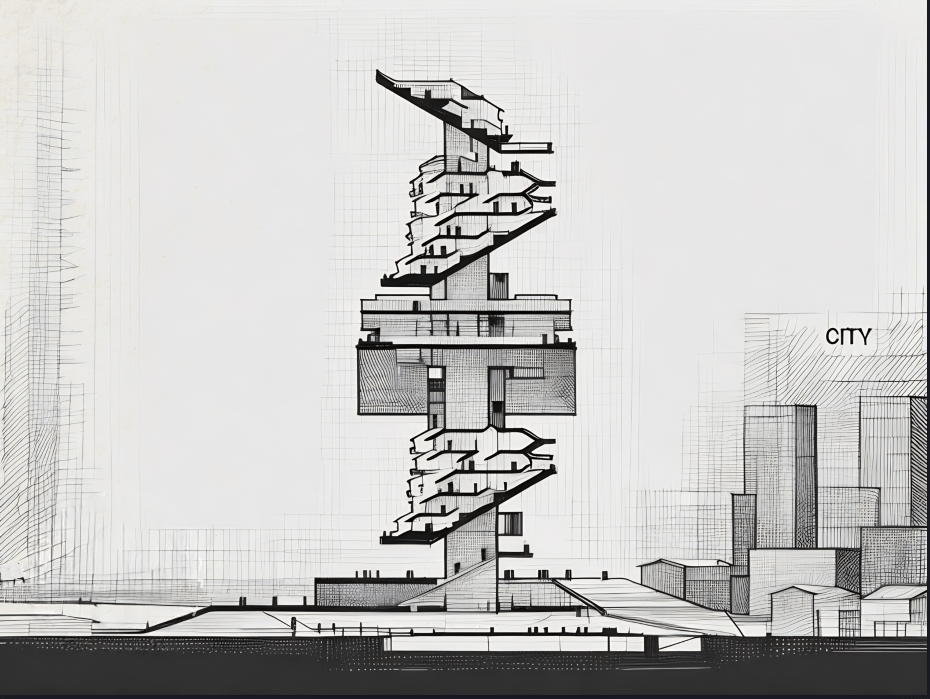

In the Phantom City Project (1958), von Stille extended his surrealist ethos into the domain of urban planning. Though unrealised, the project’s speculative designs, archived in the Archiv für Surreale Architektur (Düsseldorf), reveal an audacious attempt to imagine a utopian city centre defined not by utility but by its dissolution into mirage. Conceived for the postwar rebuilding of Manchester (UK), the Phantom City envisioned mirrored towers, floating pavilions, and transparent walkways that disoriented the viewer by collapsing the boundaries between solid and void, visible and invisible.

Perhaps the most daring design from this visionary project was deemed ‘the Impossible Building‘: a towering skyscraper straddling the city’s famed canal, it was intended to be a tenement building for the area with public and residential areas organised into vertically stacked ‘neighbourhoods’, each oriented in different directions to provide diverse views across the city. A network of pathways, thoroughfares, and alleyways guided residents and visitors alike from bottom to top, and within each neighbourhood the streets, houses and shops were arranged in tapered formations along the slope to form a cascade of roofs and yards that exemplified the project’s unique emphasis on community. By taking von Stille’s concept of collapsing the boundaries between visible and invisible to its apex, the unique geometry truly pushed the limits of design and build for the time period so that the various levels of the tenement appeared to be floating depending on which angle you looked at the building. In his archived project notes, Von Stille stated “These canals — once the arteries of the Industrial Revolution — will serve as silent mirrors catching every nuance of light, every shifting mood of a city that never stops changing.”

Notably, the project was explicitly informed by Duchamp’s Large Glass (1915–1923), whose interplay of transparency and opacity von Stille transposed into an urban context. The Phantom City’s use of reflective surfaces created an environment that both revealed and obscured, functioning as an architectural manifestation of surrealist automatism. once the arteries of the Industrial Revolution – now serve as silent mirrors, catching every nuance of light, every shifting mood of the skies above. Critics of the era dismissed the project as impractical and unfundable, yet its theoretical implications merit further scrutiny: by rendering the cityscape ephemeral, von Stille gestured toward a phenomenological ontology of urbanism predicated on impermanence and flux.

The Cathedral of Dreams and the Technological Sublime

Perhaps the most controversial of von Stille’s completed works, the Cathedral of Dreams (1969) in Paris, represents the apotheosis of his surrealist engagement with technology and spirituality. A blend of organic and geometrical forms, representing the fusion of technology and spirituality, the building features asymmetrical curves, seemingly impossible angles, and metallic surfaces interspersed with glass and intricate stonework, all contributing to its otherworldly presence. The cathedral’s corkscrew spire, described by Heidbrechter as a “tentacle of impossible ascension,”4 epitomises von Stille’s architectural idiom: a towering, twisting spire that ascends in a dramatic, helical fashion. The spire creates a sense of impossible ascension, visually suggesting movement into an unknown, spiritual dimension.

The exterior space eschews traditional religious symbolism, instead opting for abstract representations that tap into the collective dreamscape, using shapes and forms that suggest both spirituality and the psychological aspects of human nature.

Yet it is the cathedral’s interior, with its shifting holographic projections of dream imagery, that constitutes its most radical innovation. Drawing upon nascent EEG technology, the cathedral’s holograms purport to capture and project the dreams of its visitors. While the efficacy of this technology has been questioned by sceptics5 its symbolic import is undeniable: the cathedral becomes not merely a space of worship but a locus of collective unconscious projection.

A mix of light and shadow dominate the interior, contributing to an ethereal atmosphere: it is open and expansive, with fluid, continuous paths perfectly offsetting these shifting holographic projections of dream imagery. Akin to living patterns or visions, they pulsate as if alive and evoke a sense of mysticism and the unconscious mind. Here, von Stille synthesises Bretonian surrealism with the technological sublime, creating a space in which the boundaries between human subjectivity and architectural form dissolve.

It is worth noting that the multiple refusals to consecrate the cathedral underscores the subversive implications of von Stille’s vision. By integrating technology with mysticism, the Cathedral of Dreams challenges not only ecclesiastical authority but also the Cartesian dualisms of mind and matter, form and content.

Toward a Surrealist Ontology of Architecture

In reappraising von Stille’s contributions to the architectural canon, it becomes evident that his work transcends the reductionist categorisations of “uninhabitable eccentricity” that have dogged his legacy. Instead, von Stille’s oeuvre articulates a radical critique of the rationalist and functionalist paradigms that dominated mid-20th century architectural discourse. Through his destabilisation of spatial semiotics, his embrace of absurdity, and his interrogation of the limits of epistemological coherence, von Stille’s architecture performs a vital cultural function: it compels us to confront the absurdities of existence and to reimagine the possibilities of spatial experience.

In this regard, von Stille’s buildings are not merely structures but philosophical propositions—metaphorical scaffolds upon which the fragmented psyche of modernity might precariously rest. By synthesising surrealist aesthetics with architectural innovation, von Stille offers a vision of architecture that is at once playful, disorienting, and profoundly necessary.

[1] Schneidermann, P. (1978). “Functionalism Undone: Von Stille and the Limits of Utility.” Journal of European Avant-Garde Studies, 23(4), 112–129.

[2] Kroegemann, U. (1981). Spaces of Disruption: The Absurd in Twentieth-Century European Architecture. Berlin: Verlag für Moderne Theorie, p. 47.

[3] D’Alençon, H. (1979). Performative Absurdities: Surrealism and the Architectural Palimpsest. Paris: Éditions de l’Inconnu, p. 96.

[4] Heidbrechter, M. (1974). Dreams Made Stone: The Cathedral of Illusions and the Technological Sublime. Zurich: Amalgam Press, p. 23)

[5] Wöhlm, G. (1975). “The Cathedral of Illusions: A Hoax in Holography?” Technologies of Faith Review, 9(1), 14–27.