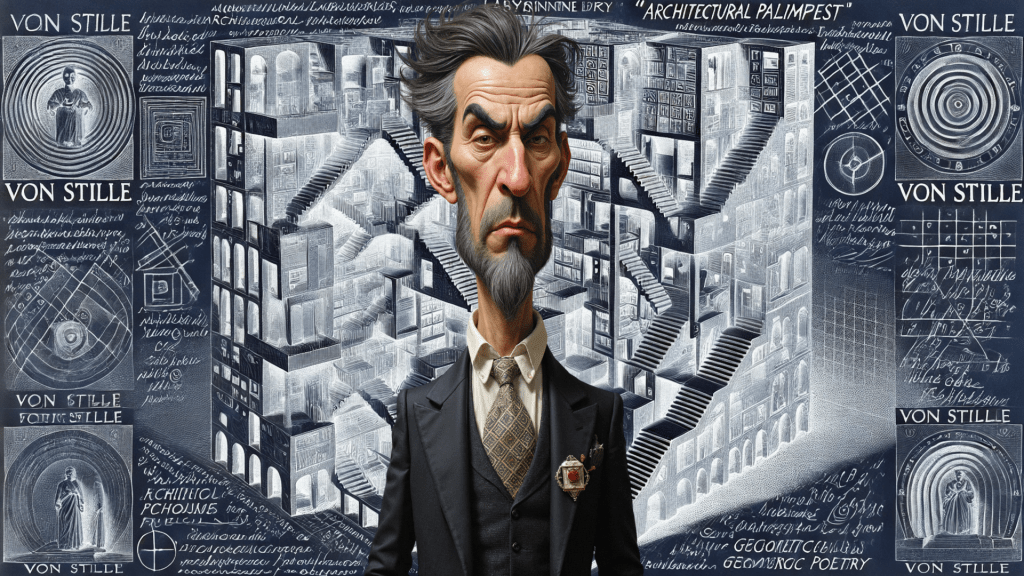

Alaric von Stille, who has died aged 70, was one of the 20th century’s most enigmatic and divisive architects. A pioneer of surrealist architecture, von Stille redefined the role of buildings not merely as structures but as provocations—monuments to the subconscious and absurd. His designs defied gravity, logic, and convention, producing works that have been called everything from “masterpieces of dream logic” to “unliveable monstrosities.”

Von Stille was born in Vienna in 1906, the scion of a family whose wealth was derived from manufacturing. Early tragedy marked his youth; his father’s suicide during the financial panic of 1914 left the family in genteel poverty. These formative years exposed him to existential uncertainty and a fascination with the irrational—themes that would dominate his architectural career. After attending the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, where he trained as a painter, von Stille became entranced by the avant-garde movements sweeping Europe in the 1920s.

Though initially inspired by the clean lines of Bauhaus and the functionality of Le Corbusier, von Stille found their rationalism stifling. It was the discovery of Marcel Duchamp’s conceptual art and the writings of André Breton, the surrealist poet and theorist, that redirected his career. Duchamp’s playful subversions of form and meaning, along with Dada’s chaotic rejection of order, profoundly influenced von Stille’s philosophy. “Architecture,” he wrote in Manifesto (of the Absurd Edifice) (1933), “must be both mirror and mirage—reflecting life’s absurdity and distorting it into beauty.”

His first major work, Villa Vertigo (1935), was a private commission on the outskirts of Zurich. The house, now a UNESCO-protected site, appears to tumble into itself. Its leaning walls, mismatched staircases leading nowhere, and ceilings that slope at disorienting angles create a sense of surreal unease. Critics derided it as “uninhabitable nonsense,” but Villa Vertigo was embraced by artists and intellectuals, who recognised its roots in the surrealist imagination. Salvador Dalí reportedly visited the house and declared it “the architectural equivalent of a melting clock.”

Von Stille reached international fame with The Labyrinthine Library (1946), constructed in Rotterdam amidst the rebuilding efforts after the German bombardment. Inspired by Jorge Luis Borges’s concept of infinite libraries, the building features spiralling corridors that appear to overlap impossibly, with staircases that double back upon themselves in ways that defy Euclidean geometry. Many visitors were enchanted; others simply got lost. The library became a landmark, cementing von Stille’s reputation as Europe’s enfant terrible of architecture.

In the 1950s and 60s, von Stille turned his surrealist gaze toward urban planning. His Phantom City Project (1958)—an unrealised utopia proposed for post-war Manchester, UK—imagined a seemingly floating city centre of mirrored towers and transparent walkways, designed to dissolve into the surrounding industrial landscape like a mirage. Central to the visionary project was von Stille’s ‘Impossible Building’: a towering skyscraper which was to straddle the city’s famed canal. It was intended to be a tenement building for the area with public and residential areas organised into vertically stacked ‘neighbourhoods’, each oriented in different directions to provide diverse views across the city and designed in such a way that the various levels of the tenement appeared to be floating depending on which angle you looked at the building. The project, though never realised due to funding concerns, became a touchstone for conceptual architects and was the impetus for the formation of Archigram: the avant-garde British architectural group whose unbuilt projects and media-savvy provocations “spawned the most influential architectural movement of the 1960’s.”

Von Stille’s magnum opus was undoubtedly The Cathedral of Dreams (1969). Commissioned by the Stella Sapiente and constructed in Paris, the cathedral’s spire twists like an unsettling tentacle into the sky, while its interior features walls of shifting holograms that project images of dreams collected from visitors via a rudimentary EEG system. It was as much a commentary on the intersection of technology and mysticism as it was a place of worship. As such the space was refused consecration multiple times, but it nonetheless became a pilgrimage site for those seeking mysticism and the extraordinary. It remains one of the most popular tourist attractions in the city.

Perhaps von Stille’s most ambitious work saw him attempt to engage with topology and the Picard–Vessiot theory in the creation of a house that leveraged four-dimensional geometry. The Tesseract House (1972), was to be constructed at the geographical centre of all land surfaces on Earth — Kırşehir City, Turkey — in an “inverted double cross” shape that would consist of eight cubical rooms, arranged as a stack of four cubes, with a further four cubes surrounding the second cube up on the stack. In consulting with a number of mathematicians and physicists on the feasibility of the concept, they agreed it was an intriguing proposal but carried too much risk regarding dimensional stability and thus the project was scrapped in the design stage.

Despite his successes, von Stille was no stranger to controversy. He was vilified by pragmatists and traditionalists, who viewed his works as extravagant and purposeless. His personal life, too, was the subject of scandal. Twice married, he maintained long-term relationships with both women and men, and he relished his reputation as a provocateur in both his art and his private affairs.

In his later years, von Stille’s work fell out of favour as brutalism and functional modernism dominated architectural discourse. He retreated to his villa in the Italian Alps, a whimsical structure known as La Casa Dei Sogni, whose interior resembled that of a living, breathing organism. There, he lived in relative isolation until his death from a stroke in 1976.

Today, von Stille is remembered as a visionary who dared to challenge the very foundations of architecture. His influence resonates in the works of deconstructivists such as Fritz Wotruba and Frank Owen Gehry, whose designs echo his disregard for orthodoxy. As his contemporary, the poet René Char, once wrote: “Alaric von Stille builds not with bricks, but with the rubble of dreams.”