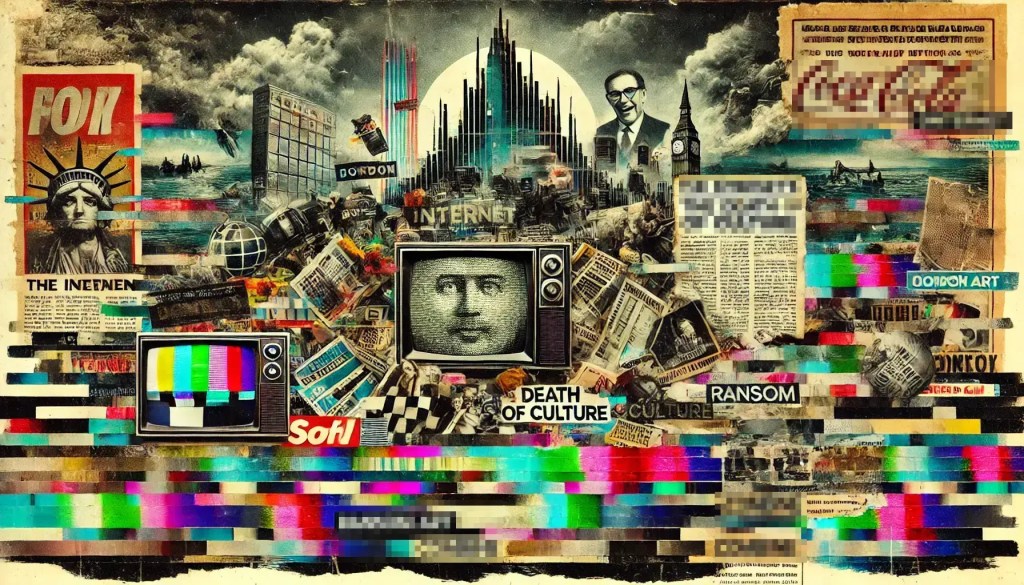

This essay examines the internet’s role in precipitating what can be termed the “death of culture,” a conceptual implosion that renders cultural expression increasingly fragmented, homogenised, and devoid of collective significance. Building on the works of Mark Fisher and other cultural theorists, the analysis interrogates the paradox of limitless choice afforded by the internet, the dissolution of countercultural authenticity, and the systemic reduction of subcultures to commodified aesthetics. The universalising tendencies of digital platforms are theorised as both accelerants of cultural entropy and harbingers of a hyper-globalised cultural vacuum.

Hypermediated Universalism and the Cultural Flatline

The internet, heralded as the democratic apogee of information dissemination, paradoxically functions as the site of cultural entropic collapse. With its ostensibly infinite horizons of choice, the internet offers a deluge of media commodities—films, television, music—exceeding the limits of human cognitive capacity to parse or prioritise.1 This hyper-proliferation of content fragments collective cultural experiences, producing a “flat ontology” of cultural engagement.2 Such fragmentation is antithetical to the galvanising conditions of mid-to-late twentieth-century subcultures, wherein music, fashion, and film coalesced into ideologically inflected movements. As streaming platforms, social media, and algorithmic curation proliferate, they simultaneously expand individual agency while eviscerating collective imagination.

The internet’s universalising algorithmic architectures, functioning under the aegis of global capitalism, elide these conditions, reducing subcultures to commodified aesthetics. As Fisher argues,3 culture increasingly “mourns itself” through endless replications of its own past. In the internet age, this self-mourning is intensified by the absence of subcultural vitality; the countercultural energies of punk, goth, or hip-hop, for instance, are spectralised into ironic pastiches, simulacra without referents.

The Paradox of Choice: Fragmentation and the Loss of Collective Imagination

The exponential growth of choice in film, television, and music—manifesting in the proliferation of streaming services, YouTube channels, and digital archives—has engendered a paralytic fragmentation of cultural consumption. Where the twentieth century was marked by relatively constrained media options—primetime television schedules, FM radio rotations—the twenty-first century is inundated with a fractal abundance of cultural commodities. This overabundance creates a centrifugal force that disperses cultural attention, rendering collective engagement nearly impossible. As Jacques Dupuy’s Simulacra of Abundance contends, “the excess of choice functions as a mechanism of immobilisation, eroding the possibility of shared cultural experiences.”4 No longer do monumental cultural artefacts emerge as unifying touchstones; instead, micro-niches cater to hyper-specific tastes, rendering the notion of a “cultural moment” increasingly obsolete. Take, for example, the once-dominant shared cultural phenomenon of event television: From 83m Americans tuning into Dallas to find out “Who Shot J.R.?” in 1980 to 24m people in the UK collectively watching as Del Boy’s generally misplaced optimism paid off at last and the Trotters became millionaires in the 1996 Only Fools and Horses Christmas Special, such media events were formative nodes of collective identity.5 Today, however, the algorithmic fragmentation of streaming platforms ensures that media consumption is hyper-personalised. A Netflix user’s algorithmically generated “top picks” differ wildly from another’s, foreclosing the possibility of shared cultural touchstones.

This phenomenon extends to music, where the collapse of physical media into Spotify playlists has dissolved genre boundaries into algorithmically determined mood playlists (e.g., “Chill Vibes” or “Workout Beats”). As Dunstaple6 contends, the erosion of genre specificity is symptomatic of a broader cultural erosion; music is no longer an ontological site for subcultural identity formation but merely a backdrop to atomised consumption. The once-predictable rhythms of cultural zeitgeists, exemplified by phenomena such as Beatlemania or the punk rock explosion, are rendered inert by this algorithmic Balkanisation.

Counterculture as Commodity and the Decline of Subcultural Potency

The internet’s propensity to flatten temporal and spatial boundaries ensures that subcultures are no longer distinct, oppositional spaces but rather repositories of commodifiable aesthetics. Mark Fisher’s critique of neoliberal cultural production, particularly its appropriation of countercultural movements, provides a critical lens for understanding this phenomenon. As Fisher argued, “The self-conscious irony of pastiche ensures that subcultures are never truly born but emerge as already-dead forms”.7 Historically, subcultures were loci of ideological contestation and alternative world-making. The punk movement, for instance, was not merely a fashion aesthetic but a bricolage of anarchic praxis, defiant music, and anti-establishment ethos.8 Similarly, goth, rave, and riot grrrl cultures emerged as cohesive lifeworlds, replete with distinct sartorial codes, semiotic lexicons, and communal philosophies. Yet in the age of Instagram and Pinterest, subcultures are reduced to aesthetic assemblages, devoid of their prior sociopolitical potency: the punk ethos of rebellion, for instance, has been supplanted by the “punk look,” a visual shorthand consisting of a studded leather jacket, spikey green mohawk and a personality devoid of political or philosophical substance.

The memetic nature of internet culture further exacerbates this issue, as subcultural symbols are rapidly disseminated, decontextualised, and recontextualised in service of virality. Laurent Echelon describes this process as “aesthetic liquidity,” whereby cultural markers lose their historical and ideological grounding through endless replication.9 The transformation of goth culture into a trend epitomises this trajectory: its original tenets of existential melancholy and artistic nihilism have been eclipsed by the superficiality of viral makeup tutorials and curated playlists, disembedded from their original ideological matrices and subsumed into the logic of capitalist exchange.

The Globalising Dynamics of the Internet

In its drive for universality, the internet imposes a homogenising force upon cultural production and consumption. Global platforms prioritise universally palatable content, eroding the specificities of local cultures and subcultures. This dynamic echoes Frédéric Beauvoir’s notion of “cultural entropisation,” whereby diversity collapses under the weight of global standardisation.10 The internet’s lingua franca—visual memes, algorithmic trends, and viral challenges—subsumes diverse cultural expressions into a monolithic digital culture.

The reduction of subcultures to aestheticised tropes mirrors the broader dissolution of distinct cultural identities under globalisation. Fisher’s assertion in Capitalist Realism that “capitalism seamlessly absorbs and neutralises opposition” resonates here, as the internet’s infrastructure serves as the ideal mechanism for the capitalist appropriation of cultural resistance. Subcultural practices are commodified into products—fashion lines, playlists, and branded collaborations—while their ideological cores are excised.

The Hauntology of Digital Culture

Building on Fisher’s hauntological critique, it is evident that the internet transforms culture into a spectral economy of endlessly recycled pasts. The countercultural potentialities of previous generations—imbued with futurity and alterity—are foreclosed under the weight of nostalgia-fetishism. The resurgence of vinyl records, VHS aesthetics, and 1980s-inspired synthwave exemplifies this temporal stagnation. While ostensibly celebrating cultural artefacts, these revivals entrench culture within the purgatorial present, perpetually reanimating its own corpse. As Amanda Drexel posits, “The algorithmic curation of nostalgia constitutes a necropolitics of the imagination, where only the past is permitted to flourish”.11 This hauntological condition is exacerbated by the algorithmic feedback loops of platforms like YouTube and Spotify, which prioritise familiarity over novelty. The digital subject is ensnared in an echo chamber of algorithmically curated nostalgia, incapable of accessing the radical alterity necessary for genuine subcultural innovation. As Yarbeck observes, “The internet does not merely flatten culture; it embalms it.”12

Globalisation and the Loss of Cultural Specificity

The internet’s globalising tendencies further exacerbate the dissolution of subcultural specificity. Historically, subcultures were situated within specific socio-geographic contexts: punk emerged in 1970s London as a response to economic austerity, while hip-hop arose from the socio-economic marginalisation of African-American communities in the Bronx.13 Today, however, the internet facilitates the decontextualised circulation of cultural artefacts, eroding their spatial and historical particularities.

This globalising dynamic mirrors broader processes of cultural homogenisation under late capitalism. Localised lifeworlds are subsumed into a universal aesthetic regime, producing what Catterall14 terms “the placeless culture of everywhere and nowhere.” The internet’s role in this process is twofold: it enables the instantaneous transmission of cultural signifiers across geographic boundaries while simultaneously reifying these signifiers as commodities within the digital marketplace. The result is a cultural landscape where specificity is subsumed by sameness, where the punk of London, the rave of Berlin, and the hip-hop of New York are flattened into interchangeable commodities.

The Absence of Futurist Orientation

The internet’s role in the death of culture is neither incidental nor peripheral; it is structural and systemic. Through the paradox of choice, the aestheticisation of subcultural resistance, and the universalising tendencies of digital platforms, the internet orchestrates a profound cultural entropy. Subcultures have been reduced to superficial aesthetics, devoid of the philosophical and ideological gravitas that once defined them. Meanwhile, the globalising dynamics of the internet accelerate the homogenisation of cultural expression, rendering the local and particular increasingly invisible. In this brave new world of infinite choice and perpetual connectivity, culture as a site of collective imagination, resistance, and meaning risks becoming a relic of the pre-digital past.

Yet, as Fisher reminds us, the spectral traces of past subcultural radicalisms linger, haunting the present with the possibility of their reactivation. To critique the internet’s role in cultural death is not merely to mourn what has been lost but to imagine what might yet be reclaimed. Perhaps, amid the spectral ruins of digital culture, there remains the latent potential for the reconstitution of subcultural vitality—a radical cultural praxis capable of transcending the flattening logics of digital capitalism.

[1] Tarkinson, E. (2012). “Hyper-Choice and the Paralysis of Cultural Engagement.” Digital Humanities Review, 33(1), p. 1-25.

[2] Harpstein, N. (2012). Flat Ontologies and Fragmented Futures: Digitalism in Late Capitalism. New York: Synecdoche Publishing.

[3] Fisher, M. (2009). Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Winchester: Zero Books.

[4] Dupuy, J. (2010). Simulacra of Abundance. Pseudoacademic Press.

[5] Jenkins, H. (1997). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: NYU Press.

[6] Dunstaple, L. (2010). “Mood Playlists and the Death of Genre.” Interdisciplinary Music Review, 44(2), p. 103-121.

[7] Fisher, M. (Unpublished). Spectres of the New.

[8] Hebdige, D. (1979). Subculture: The Meaning of Style. London: Methuen.

[9] Echelon, L. (2012). Aesthetic Liquidity: Memes and Subcultural Decay. Nonexistent Editions.

[10] Beauvoir, F. (2010). Entropy and Identity. Academic Mirage, p. 61.

[11] Drexel, A. (2019). Chronos and Digitality. Theoretical Constructs Publishing, p. 104.

[12] Yarbeck, C. (2020). “The Internet as Cultural Embalmer.” Postmodern Critiques, 5(3), 34-49.

[13] Rose, T. (1994). Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press.

[14] Catterall, P. (2011). “The Placeless Culture of Everywhere and Nowhere.” Journal of Digital Geography, 12(3), 223-245.