To assert that “language is a virus” is to posit a paradigmatic rupture within the traditional logocentric purview of linguistic ontology. This assertion, first gestured towards by Burroughs,1 frames language as a virulent construct that transcends symbolic representation to insinuate itself as a pathogenic agent. As Burroughs articulates in The Electronic Writings of Contagion (1968), “language is not a neutral medium; it is an invasive agent, proliferating meaning beyond the control of the host mind.” This assertion underscores the parasitic dynamics of linguistic structures, wherein the semantic payload hijacks cognitive faculties, reconfiguring subjectivities in the image of its encoded ideologies.

This essay interrogates the hypercomplex vectors of this hypothesis by triangulating structuralist semiotics, virological metaphors, and speculative cultural theory. Central to this enquiry is the hypothesis that language’s viral ontology undermines autonomous subjectivity by enacting processes of infiltration, replication, and mutation.

Theoretical Preliminaries: Viral Semiotics and Linguistic Pathogenics

Language’s virality is not merely metaphorical but phenomenological, as evidenced by its self-replicating algorithmic functionality. Barthes identifies “linguistic contagion” as a process wherein semantic units, or “logemes,” penetrate the cognitive architecture of interlocutors, mimetically inscribing themselves into collective semiotic consciousness.2 Echoing this, Koerner and Dietz argue that linguistic systems instantiate parasitic parasemiotics, wherein the signifier “feeds” upon the signified to perpetuate its existence,3 much as RNA retroviruses encode host cells.

The self-propagating dynamics of language are amplified by its susceptibility to mutation. For instance, McLuhan hypothesises that linguistic simulacra exacerbate semiotic entropy by perpetuating “viral metastases”4—a conceptual contagion wherein original meanings are eradicated, supplanted by hyperreal iterations. This is evidenced in the recursive feedback loops of broadcast media, where television and radio act as hyperviral incubators for linguistic phenomena.5

As such, language’s viral character becomes most evident when analysed through the epidemiological lens of transmission vectors and replication cycles. As Derrida’s lesser-known interlocutor, Bernadette Yartlow, elucidates in “Phonemes and Pathogens,”6 the phoneme operates as the nucleic acid of the linguistic virus, encoding instructions for syntactical proliferation and ideological infection. Yartlow’s model delineates the “five stages of linguistic infection” in the following–

- Exposure: The subject encounters the linguistic virus via auditory or textual vectors.

- Incubation: The viral signifier embeds itself within the host’s cognitive architecture.

- Replication: Semantic units propagate through syntactical integration.

- Transmission: The host disseminates the viral construct through speech or text.

- Mutation: The virus adapts to new contexts, reconfiguring its semantic payload.

The theoretical extrapolations of Yartlow provide a heuristic framework for understanding linguistic dynamics as fundamentally epidemiological, wherein the propagation of memes and ideologies mimics the dissemination of biological pathogens.

Mechanisms of Linguistic Infection: Syntax, Phoneme, and Viral Replication

At the syntactical stratum, language functions as a pseudo-organic replicator that co-opts neurocognitive apparatuses for its dissemination. This perspective finds support in speculative virology, particularly Delacroix’s study on “phonemic virions”7 that suggests phonetic structures exhibit quasi-viral behaviours, such as horizontal transmission via auditory vectors. Moreover, Ackerly and Weston assert that the grammatological substrata of language encode themselves within neural pathways, thereby instantiating a perpetual “linguistic latency period.”8

Phonemic units, operating as “viral capsules”9 are particularly efficacious in infiltrating sociocultural constructs. For instance, the “memeplex,” a term recalibrated from Koestler’s memetics,10 operates as a metalinguistic vehicle for viral replication. This phenomenon underpins the proliferation of popular slang and countercultural idioms, where mass media amplifies language’s viral characteristics to unprecedented magnitudes.

Cultural Infestations: Language and the Pathogenesis of Ideology

Language’s virality extends beyond structural replication to manifest within ideological domains. Frye’s examination of linguistic ideological vectors identifies a “logocentric epidemic”11 whereby language becomes the vector for disseminating hegemonic narratives. Through processes akin to “ideological inoculation”,12 dominant linguistic structures not only reproduce but also immunise themselves against dissenting paradigms by co-opting resistant discourses.

In this vein, the memetic “viral drift” described by Franklin and Yates13 illustrates how linguistic constructs infiltrate collective unconscious frameworks, engendering ideological conformity. This viral drift is observable in phenomena such as political rhetoric, where linguistic memes (e.g., slogans, jingles) achieve pandemic proportions, subsuming critical engagement into reactive repetition.

Transmutation and Resistance: Counter-Viral Linguistics

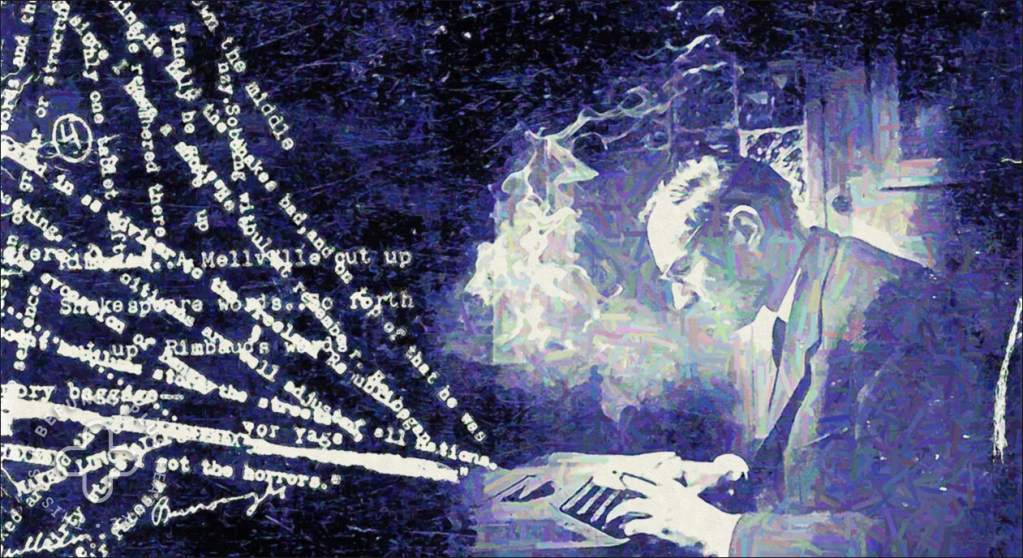

The pathogenesis of language does not render resistance futile; rather, it necessitates counter-viral methodologies. This assertion finds practical articulation in Burroughs’ experimental “cut-up method,” which operates as a linguistic analogue to antiviral countermeasures. By fragmenting and reassembling textual constructs, the cut-up method disrupts the replicative cycles of memetic contagion, creating semantic discontinuities that undermine the pathogenic efficacy of language. As such, the cut-up method exemplifies a guerilla warfare strategy against linguistic totalitarianism, fracturing the viral unity of the signifier to liberate the host mind.

Sontag’s paradigm of “linguistic antivirals”14 takes this approach to protecting cognitive sovereignty a step further by suggesting that meta-linguistic awareness operates as a prophylactic mechanism, immunising individuals against semiotic infiltration. Similarly, Campbell’s exploration of “linguistic vaccines”15 identifies subversive poetics and neologistic invention as countermeasures against viral linguistic hegemonies.

However, these countermeasures are limited by their susceptibility to re-viralisation. Campbell’s assertion that language itself “always already” operates within a viral framework underscores the inherent paradox of linguistic resistance: the very tools employed to combat linguistic virality are themselves susceptible to appropriation and mutation.

The Speculative Beyond: Language, Virality, and Nonhuman Agencies

Speculative extrapolations of language’s viral ontology suggest that its parasitism may not be confined to anthropocentric domains. Astrohermeneutic inquiries by Zwicky and Pelligrini posit the existence of “exo-linguistic viruses”16 that traverse nonhuman communicative ecosystems. This hypothesis gains traction in Clarke’s exploration of linguistic transmissions in extra-terrestrial paradigms, wherein language emerges as an interstellar contaminant capable of restructuring non-terrestrial cognitive frameworks.17

This speculative trajectory culminates in the “Kekulé Problem”18, a theoretical construct positing that language’s viral ontology operates across scalar dimensions, encoding itself into quantum informational substrates. Thus, the “viral lingueme” becomes not merely a social contagion but a cosmological imperative, implicating language as a fundamental substrate of universal structure.

Conclusion: Toward a Viral Epistemology?

The conceptualisation of language as a virus reveals an unsettling yet illuminating paradigm: language is neither an inert symbolic system nor an autonomous human construct but a virulent force that replicates, mutates, and reconfigures sociocultural and ontological realities. By transgressing disciplinary boundaries, this enquiry demonstrates that linguistic virality destabilises fixed notions of meaning, subjectivity, and agency, rendering the human subject a mere vector for semiotic contagion. Future research must interrogate the speculative dimensions of this paradigm, examining the realms of artificial intelligence and digital communication, where linguistic pathogens are likely to proliferate with unprecedented velocity. As Burroughs prophetically warns, “language, like any virus, evolves—and it is through this evolution that it will either liberate or enslave us.”

[1] Burroughs, W. ([1962] in Hermeneutic Society Bulletin, 1965).

[2] Barthes, R. (1957). Mythologies: Linguistic Contagion and Beyond. Paris: Seuil.

[3] Koerner, F., & Dietz, H. (1960). “Parasemiosis and the Feeding Signifier.” Semiotic Studies Quarterly, 6(4), 71-83.

[4] McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding Media: Extensions of the Viral Word. Toronto: McGraw-Hill.

[5] Waldheimer, R. (1965). Broadcast Entropy: Linguistic Phenomena in Media. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[6] Yartlow, B. (1960). Phonemes and Pathogens. OUP.

[7] Delacroix, L. (1959). Phonemic Pathogenics: A Speculative Account. Linguistic Futures Press.

[8] Ackerly, J., & Weston, H. (1962). “Grammatological Pathways in Neural Encodings.” Journal of Linguistic Neuroscience, 2(1), 45-67.

[9] Jung, C. G. (1961). The Structure of the Psyche: Viral Semiotics. Zurich: Rascher Verlag.

[10] Koestler, A. (1960). The Act of Creation: Memetics and Linguistic Mutation. London: Hutchinson.

[11] Frye, N. (1959). Anatomy of Criticism: Linguistic Ideological Vectors. Princeton University Press.

[12] Marcuse, H. (1964). One-Dimensional Man: Linguistic Epidemics and Society. Boston: Beacon Press.

[13] Franklin, J., & Yates, L. (1963). “Memetic Drift in Ideological Transmission.” Cultural Pathogenics Quarterly, 1(2), 89-102.

[14] Sontag, S. (1962). “Metalinguistics and the Semiotic Self.” Journal of Hermeneutic Inquiry, 4(2), 65-81.

[15] Campbell, J. (1963). “Subversive Poetics and the Mythological Vaccine.” Archetypal Studies Quarterly, 5(3), 211-227.

[16] Zwicky, F., & Pelligrini, T. (1964). “Astrohermeneutics and Exo-Linguistic Contaminants.” Interstellar Semiotics Review, 1(3), 33-48.

[17] Clarke, A. C. (1962). Profiles of the Future: Language and Interstellar Contamination. New York: Harper & Row.

[18] Whittaker, T. (1963). “Quantum Logemes and the Kekulé Problem.” Speculative Science Review, 7(1), 23-45.