The twilight of the Soviet Union marks not merely the cessation of a superpower’s geopolitical influence but also a monumental shift in the ideological architecture of global modernity. In the aftermath of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a moment emblematic of the so-called “end of history”, the dialectic between individualism and collectivism has emerged as a predominant site of cultural and political contestation. The victory of liberal democratic capitalism, ostensibly signified by the disintegration of the USSR and the triumph of American-style individualism, necessitates an intricate analysis of its latent ramifications and invites scrutiny, particularly from those outside the cultural framework of Western liberalism. Individualism, valorised as the apotheosis of human freedom, demands interrogation; not merely as an idealised construct, but as an ideological formation that presages disquieting transformations in the sociocultural and political milieu of the 21st century.

Individualism represents a crisis rather than a conquest—one that is likely to lead to dystopian manifestations in the digital era

This essay endeavours to interrogate the ascendancy of individualism within the emergent post-Soviet order, not as a historical inevitability but as an ideological contingency fraught with peril. While the valorisation of personal freedom, consumer choice, and self-expression underpins the triumph of neoliberal individualism, logic dictates that its latent contradictions undermine collective cohesion, exacerbate sociopolitical fragmentation, and inevitably culminate in a pervasive sense of alienation. This critique draws upon interdisciplinary frameworks in cultural studies, sociology, and critical theory to posit that the unchecked proliferation of individualism represents a crisis rather than a conquest—one that is likely to lead to dystopian manifestations in the digital era.

The Ideological Genesis of Individualism and Its Cold War Ascendancy

Individualism, while often framed as an ahistorical and universal value, is a historically contingent construct that emerged within specific intellectual, economic, and political milieus. Enlightenment-era liberalism, as articulated by Locke, Rousseau, and Kant, placed the autonomy of the individual at the centre of moral and political life, supplanting the communal frameworks of pre-modern societies. This ethos was subsequently institutionalised through capitalist economic systems, which valorised personal enterprise, ownership, and consumption.

Collectivism, rooted in a dialectical interplay between the individual and the collective, eschewed the fragmentation of the subject in favour of a relational ontology predicated on solidarity and shared purpose. In the Marxist-Leninist tradition, the individual attained meaning through participation in collective endeavours directed toward a shared telos. Yet, as Lyudmila Kartunov1 has argued, this relational paradigm was undermined by internal contradictions—namely, the ossification of bureaucratic structures, the erosion of democratic praxis, and the reification of state power.

The substitution of collective solidarity with individualistic self-interest represents not an emancipation, but an enclosure of the subject

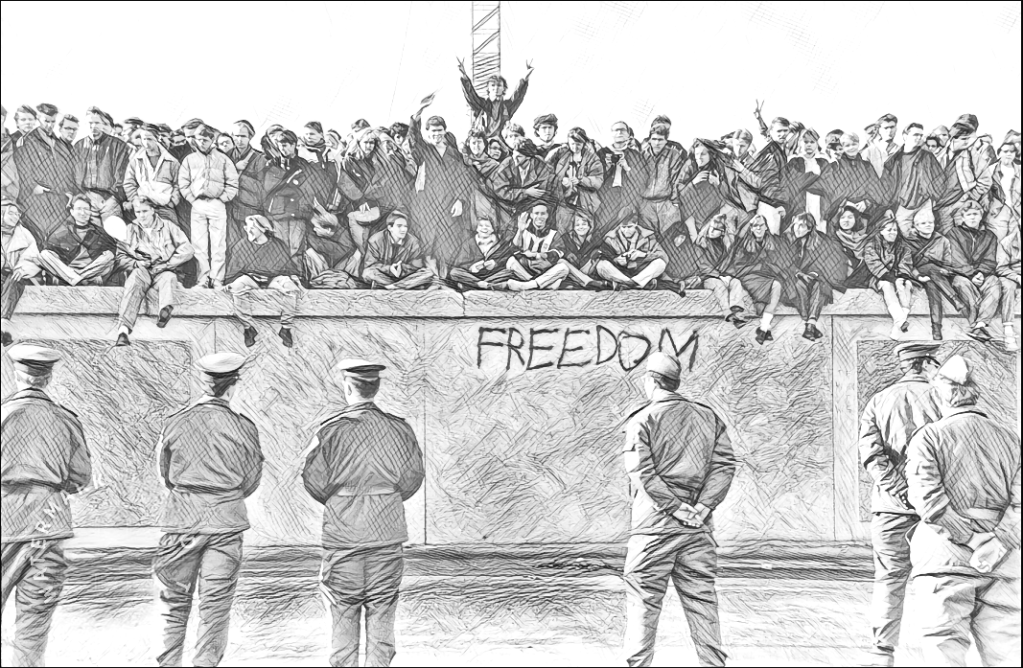

The Cold War operationalised this ideological division, casting the United States as the apotheosis of individual liberty and the USSR as the defender of collectivist solidarity. In this context, the allure of individualism emerged not merely as an antithesis to collectivism, but as a simulacrum of freedom. The American cultural imaginary, epitomised by consumer choice and self-expression, seduced the disenchanted subjects of the Eastern bloc by promising liberation from the perceived constraints of collectivist paradigms. Perhaps this is why 38,000 Russians queued for hours when McDonald’s first planted their golden arches firmly in the country in 1990. Yet, as Roland Doxius2 has provocatively argued, the substitution of collective solidarity with individualistic self-interest represents not an emancipation, but an enclosure of the subject within an ideological framework that privileges market rationality over human connectivity.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 has so far been heralded in Western discourse as the definitive repudiation of collectivist ideologies. Scholars such as Fukuyama3 contended that the triumph of liberal democracy represented an evolutionary culmination, a final synthesis wherein the aspirations of humanity were fulfilled through the universalisation of market-based individualism. However, such triumphalist narratives elide the structural complexities and contradictions inherent in the transition from collectivism to individualism. Yet the apparent triumph of individualism in this contest should not obscure its dialectical entanglement with collectivism; the two remain mutually constitutive, each deriving its moral legitimacy through opposition to the other. As cultural theorist Tatiana Ivanyuk observes, “The ideological performance of the Cold War was not merely a conflict of values but a dialectical theatre wherein the virtues of one system were continually redefined by the perceived vices of the other”.4

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, however, has disrupted this dialectic, inaugurating a global monoculture of individualism that lacks a countervailing ethos. This unipolar ideological landscape demands a critical reappraisal, particularly with regard to the socio-political and cultural pathologies engendered by unrestrained individualism.

The Paradox of Freedom: From Liberation to Alienation

At the core of the individualist paradigm lies an insidious paradox: the elevation of personal freedom, ostensibly liberatory, often results in alienation, fragmentation, and subjugation to new forms of control. The individual, now disentangled from the communal and institutional frameworks which historically conferred identity and meaning, becomes both architect and arbiter of their existence. This freedom, while intoxicating, is also disorienting, exposing the individual to the isolating imperatives of self-realisation and consumerism. The Western celebration of individual autonomy presupposes a detachment from collective responsibility, thereby engendering what Gabriel K. Harstein terms “existential atomisation”—a condition wherein the subject, unmoored from relational anchors, confronts the void of meaning in an increasingly commodified world.5

While the burgeoning internet can be viewed as a utopian democratising force, its infrastructure seems tailor made for increasingly entrenched individualism

In his seminal work ‘After Virtue’, Alasdair MacIntyre articulates the consequences of this fragmentation, noting: “In the absence of a shared moral horizon, the individual becomes a disconnected emotivist, navigating a sea of competing preferences without the anchorage of communal narratives”.6 Indeed, the post-Soviet landscape, stripped of the grand ideological narratives that once oriented human action, increasingly resembles the condition described by MacIntyre—a cultural void in which the self is the sole locus of meaning. As individuals are enjoined to prioritise self-actualisation, they are simultaneously rendered vulnerable to the machinations of capital which instrumentalises individuality as a mechanism for consumerist interpellation. This phenomenon is exemplified by the proliferation of lifestyle branding, wherein personal identity is commodified and marketed as a consumable good. Thus, what is presented as a celebration of individuality is, in fact, a mechanism of homogenisation—a subsumption of the unique subject under the hegemonic logic of the market.

This atomisation of social life is likely to be further exacerbated by the digital revolution, which one hypothesis theorises will reconstitute the public sphere into a series of algorithmically mediated echo chambers. While the burgeoning internet can be viewed as a utopian democratising force, its infrastructure seems tailor made for increasingly entrenched individualism, privileging personalised content over collective deliberation: a place where the digital self is both emancipated and entrapped, simultaneously empowered and surveilled.

The Crisis of Collective Action in the Oncoming Digital Age

The ascendancy of individualism has profound implications for the viability of collective action in the contemporary world. As individuals retreat into self-referential bubbles, the capacity for solidarity and coordinated resistance against systemic injustices is diminished. The neoliberal emphasis on personal responsibility and self-optimisation deflects attention from systemic injustices, transforming structural inequalities into personal failures. This ideological sleight of hand, which shifts the locus of agency from the collective to the individual, is likely to render contemporary societies increasingly incapable of addressing collective challenges. This fragmentation of collective movements into a cacophony of personal grievances could therefore see powerful institutions and elites consolidate their dominance, unchallenged by any coherent opposition, coupled with the erosion of privacy as technological encroachments enable unprecedented levels of surveillance and manipulation.

This ideological sleight of hand […] is likely to render contemporary societies increasingly incapable of addressing collective challenges

Ergo, the paradox of individualism lies in its capacity to render the subject simultaneously autonomous and powerless. The emphasis on personal freedom, while ostensibly liberatory, diverts attention from structural inequalities and collective struggles. As Jürgen Habermas has argued,7 the commodification of the public sphere undermines the conditions for democratic deliberation, rendering societies vulnerable to domination by technocratic elites. In this context, the very notion of freedom is reconfigured as a marketable commodity, detached from its emancipatory origins.

Furthermore, the collapse of grand ideologies has engendered a pervasive sense of powerlessness, as individuals confront the disintegration of the collective narratives that once provided meaning and direction. In the absence of shared frameworks, the modern subject is consigned to a condition of perpetual contingency, wherein the pursuit of self-actualisation is accompanied by an acute awareness of its futility.

The Future of Freedom: Speculations on the 21st Century

While individualism has been celebrated as a triumph of human freedom, its darker manifestations necessitate a critical revaluation. As the 21st century unfolds, the unchecked ascendancy of individualism presents profound challenges for society. Speculations on the erosion of privacy, the commodification of identity, and the fragmentation of collective action all point to a dystopian future in which individual freedom is increasingly illusory. This emphasis on personal autonomy, when decoupled from collective responsibility, engenders forms of selfishness and myopia that undermine the very foundations of a cohesive society.

This imposed collectivism, driven by surveillance-based control, threatens to subsume individual agency under the imperatives of capital and technology

Paradoxically, the very forces that individualism has unleashed—market logics, digital technologies, and cultural homogenisation—may culminate in a new form of collectivism, one imposed from above rather than emerging organically from below. This imposed collectivism, driven by surveillance-based control, threatens to subsume individual agency under the imperatives of capital and technology, transforming the individual into a mere cog in the machinery of neoliberal governance.

The task of resisting this dystopian trajectory requires a reimagining of freedom, one that transcends the binary of individualism and collectivism. As Mariya Borovka has argued, the future of human freedom lies not in the atomised individual, but in the collective subject—a community of individuals united by shared purpose and mutual respect.8 By embracing this dialectical vision of freedom, we can begin to articulate a post-individualist ethos that prioritises collective well-being without sacrificing personal autonomy. This synthesis must address the structural conditions that perpetuate alienation and inequality, fostering a relational ontology that affirms the interconnectedness of all human beings

In this context, the role of technology must be reimagined. Rather than serving as a tool for the commodification of individuality, future digital platforms must be leveraged to foster genuine dialogue and collective action. This requires a reorientation of the ethical and regulatory frameworks that govern technological development, ensuring that the theoretical digital sphere becomes a space for solidarity rather than division.

The Perils of Individualism

The ascendancy of individualism in the post-Cold War order represents both a triumph and a tragedy. While it has liberated the subject from certain forms of oppression, it also encourages new forms of alienation and unimagined forms of domination. As we confront the challenges of the 21st century, it is imperative to critically interrogate the ideological underpinnings of individualism and to envision new modes of collective existence that affirm the dignity and interconnectedness of all human beings.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, far from marking the end of history, signals the beginning of a new dialectical struggle—a struggle to reconcile the aspirations of individual freedom with the imperatives of collective solidarity. In this endeavour, we must heed the lessons of the past while remaining attentive to the possibilities of the future, forging a path toward a world that is both free and just.

[1] Kartunov, Lyudmila. State and Subject: A Critique of Soviet Collectivism. Moscow: Progress, 1989.

[2] Doxius, Roland. “The Simulacrum of Freedom: On the Ideological Function of Individualism.” New Left Review, no. 189 (1991): 45-62.

[3] Fukuyama, Francis. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Free Press, 1992.

[4]Ivanyuk, Tatiana. Cold War Dialectics: Rethinking Ideological Conflict. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1987.

[5] Harstein, Gabriel K. Alienation in the Age of Consumer Capitalism. London: Verso, 1987.

[6] MacIntyre, Alasdair. After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1981.

[7] Habermas, Jürgen. The Theory of Communicative Action: Lifeworld and System. Boston: Beacon Press, 1984.

[8] Borovka, Mariya. “The Collective Subject: Toward a New Ontology of Freedom.” Philosophy Today, vol. 34, no. 4 (1990): 391-404.